Advancing the stories and ideas of the kingdom of God.

John Murdock

Contributor

“Anger is the most fundamental problem in human life,” Willard taught. Last summer’s assassination attempt was a vivid illustration.

“Anger is the most fundamental problem in human life.” So said Dallas Willard. Yet despite my admiration for Willard, whose books I’ve dutifully kept on my shelves if not always before my eyes, this particular conclusion was one I long questioned. Perhaps that was because I could internally categorize my own anger as righteous, a trick I couldn’t manage with my lust and pride.

Last July, when a would-be assassin fired on Donald Trump in a field in Butler, Pennsylvania, Willard’s words sprang to mind again. I began to question my prior skepticism anew. At that moment, mismanaged anger certainly presented itself as a fundamental problem, and the sadly successful assassination of a Minnesota state lawmaker and her husband this June has only amplified my concern.

After the Butler shooting, I reengaged with Willard’s sweeping classic work The Divine Conspiracy and sought to uncover the story of the man behind it. Willard’s biography involves an unlikely journey from undergoing family tragedy in rural Missouri to becoming a philosophy professor at the University of Southern California. There, he argued for the reality of reality in an academic milieu often content with declaring all to be a mere illusion.

Get the most recent headlines and stories from Christianity Today delivered to your inbox daily.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Thanks for signing up.

Please click here to see all our newsletters.

Sorry, something went wrong. Please try again.

But beyond any biographical detail, the true source of Willard’s declaration about the problematic primacy of anger was Jesus, whom Willard asserted was not just nice or good but smart—really smart. “My hope is to gain a fresh hearing for Jesus,” Willard boldly wrote at the opening of his book, “especially among those who believe they already understand him.”

James Bryan Smith

Scot McKnight

Willard argued that in the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus was not just pulling marbles from a bag, presenting individual gems of wisdom that could be considered independently. Instead, the order of the presentation mattered greatly. “It is the elimination of anger and contempt,” he asserted, “that [Jesus] presents as the first and fundamental step toward the rightness of the kingdom heart.”

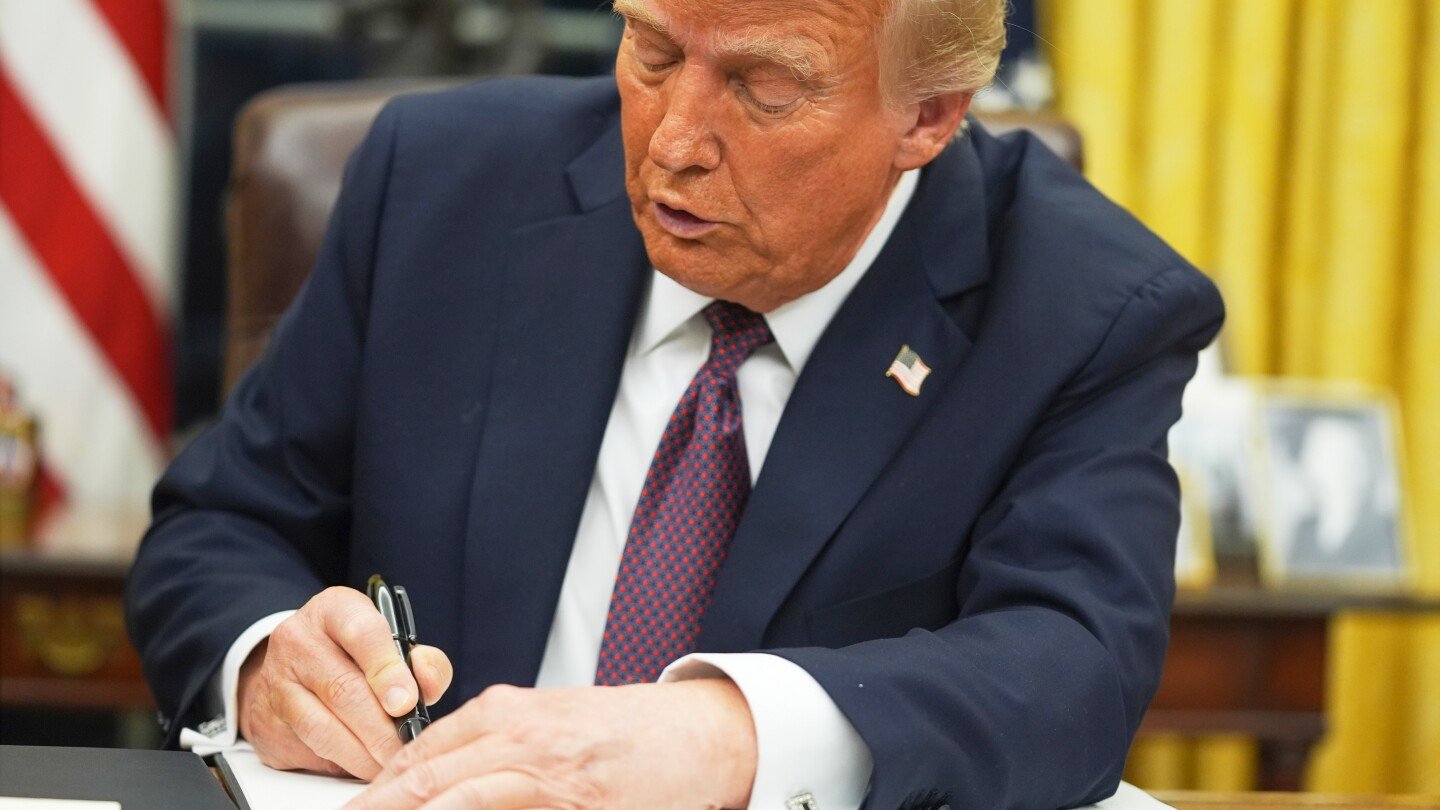

Conversely, today it is the systematic elevation of anger and contempt that is often rewarded across the political spectrum. One can argue whether Trump is a symptom, a cause, a catalyst, or a victim (or some combination of all those), but doubtless he is today’s central figure in America’s political culture of anger.

Trump’s famous fist-pumping response in Butler—plus a well-placed American flag and photographer—may have cemented his 2024 victory. His cry of “Fight! Fight! Fight!” would be emblazoned on the minds of millions and on the front of nearly as many T-shirts. In May, Trump replaced a White House portrait of former president Barack Obama with a canvas depicting the moment.

For me, though, the most-lasting memory from watching the events at Butler unfold on television was seeing a gray-haired man who, with his middle finger extended and cheeks flushed with rage, turned his face away from Trump, who was being loaded into an SUV behind him, and toward the cameras. From behind sunglasses, he yelled at the top of his lungs with words that matched his sign language. (You can catch a glimpse of him, in a red shirt and dark ball cap, on the right side of this video at the 2:15 mark.)

Bonnie Kristian

Harvest Prude and Kate Shellnutt

Were his curses directed toward the media, the would-be assassin, or just an amorphous them? Whatever his answer might be, from that moment, it seemed our national anger would only rise.

Though some of Trump’s supporters have declared him a changed man since the shooting, sadly he remains a contributor to that bitterness and mutual contempt, routinely calling people who pose obstacles to his agenda “fool,” “scum,” and “sleazebag.” These are not the words of a man who has absorbed the meaning of Jesus’ preaching on anger, where he taught that “anyone who says, ‘You fool!’ will be in danger of the fire of hell” (Matt. 5:22). Jesus was not prescribing a new, pick-your-insults-carefully legalism here, Willard explained, but “giving us a revelation of the preciousness of human beings.”

In fairness to Trump, this kind of contempt has been with us since the days of Cain. The president is far from alone in missing the enormity of the fact that every person on the planet is created in the image of God. As C. S. Lewis put it, “There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal.”

Still, the Christian conviction is that the dignity of the imago Dei is universal and must be extended not only to those holding the levers of power but also to those on the lowest rungs of influence and respectability. The imago Dei must be extended to Trump himself, and it must be extended to people like Kilmar Abrego Garcia, the man whose legal saga—a wrongful deportation to an El Salvador prison, followed by court battles, then weeks of administration foot-dragging, and finally a return to the US to face freshly minted criminal charges that reportedly led one prosecutor to resign—has come to symbolize a larger debate around due process and individual rights.

That dignity is not tied to any special merit Abrego Garcia may boast. Indeed, some enthusiasm for his cause waned as evidence emerged that Abrego Garcia may have beaten his wife and been involved in human trafficking. Members of the Trump administration and their allies have pointed to those allegations to speak of Abrego Garcia in angry, dehumanizing terms.

Andy Olsen

Carrie McKean

Harsh comments from White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt and Attorney General Pam Bondi have been particularly striking to me, as both women prominently wear crosses around their necks. “With the tongue we praise our Lord and Father, and with it we curse human beings, who have been made in God’s likeness. Out of the same mouth come praise and cursing. My brothers and sisters, this should not be” (James 3:9–10).

Willard described contempt as “a kind of studied degradation of another.” For those of us dismayed by that degradation in our politics, however, the task at hand is resisting the temptation to degrade the degraders. I’ve fallen prey to this myself in moments of anger at the president and his policies, and I have nothing good to show for it. “The delicious morsel of self-righteousness that anger cultivated always contains comes at a high price in the self-righteous reaction of those we cherish anger toward,” as Willard warned. “And the cycle is endless as long as anger has sway.”

Breaking that cycle is not easy, but it is essential for our personal and communal well-being. “To cut the root of anger,” Willard wrote, “is to wither the tree of human evil.” That is not a call to ignore injustice or, worse yet, to embrace evil under a cultish loyalty masquerading as love. Rather, according to Willard, “the answer is to right the wrong in persistent love.” We do so recognizing, as Willard also observed, that if you “find a person who has embraced anger, … you find a person with a wounded ego.”

This is the orientation that can produce a book title like I Love Idi Amin from the Anglican bishop Festo Kivengere, who in the 1970s opposed the Ugandan dictator without demonizing him. Kivengere expressed love and concern for one called “Africa’s Hitler”—and he is far from being the only model available to us. I have met the Nassar family of Bethlehem, Christians who, facing anger from every side, nevertheless live by the motto “We refuse to be enemies.”

Russell Moore

Matthew Loftus

Last summer, the assassination attempt in Butler reminded me of the great challenge of anger. I prayed then and still pray today that the experience will change Trump himself, helping him understand anger’s sheer destructiveness to those who wield it and those it targets. But at least for now, the cycle of anger continues in America. As individuals, we can’t quickly change that national dynamic. But we can take steps to address that cycle in our own hearts.

“Nothing can be done with anger that cannot be done better without it,” Willard concluded. We do not need bitterness and contempt to oppose evil well. Kivengere looked to Jesus forgiving his unrepentant executioners from the cross and realized what that example meant for his own thinking about the dictator who had killed his friends and forced him into exile. “As evil as Idi Amin was,” he asked, “how can I do less [than forgive] him?”

Christ called his disciples to “take up their cross” (Matt. 16:24–26), and Paul wrote of his desire to know “the fellowship of his sufferings” (Phil. 3:10, NASB). In that vein, Willard taught, “Jesus did not die on the cross so that we wouldn’t have to die on the cross. He died on the cross so that we could join him in his death on the cross.” Willard called this the “meaning of the cross in spiritual growth.” And one way that we join with Jesus is by surrendering our will to God and rejecting the anger we coddle in our hearts.

John Murdock is an attorney who writes from Texas.

Emily Belz

Russell Moore and Rich Villodas

Interview by Emily Belz

Russell Moore

Carrie McKean

View All

Marvin Olasky

What you should know about the basics of Buddha’s life and teaching.

Andrew Wilson

We often treat these words as synonyms. In Scripture, they’re near opposites.

Jayson Casper

Rule by the minority Muslim sect is rare in history, but two premodern dynasties help explain Iran.

John Murdock

“Anger is the most fundamental problem in human life,” Willard taught. Last summer’s assassination attempt was a vivid illustration.

News

Harvest Prude

Evangelical ministries and advocates respond to the legislation’s impacts on immigration enforcement, food aid, and abortion funding.

Public Theology Project

Russell Moore

What we love about the hero is not his power so much as his vulnerability.

Jayson Casper

Shiite sects differ on what matters most in a leader.

The Russell Moore Show

Why doomscrolling, algorithms, and AI are keeping us from community

You can help Christianity Today uplift what is good, overcome what is evil, and heal what is broken by elevating the stories and ideas of the kingdom of God.

© 2025 Christianity Today – a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization

“Christianity Today” and “CT” are the registered trademarks of Christianity Today International. All rights reserved.

Seek the Kingdom.