An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Access the Data

Access and analyze data sets, maps, charts and graphs.

Data by Type

Access the Data

Data by Topic

Explore the Data Repository

Understand the Research

Get insights and objective analysis from experts in the field.

Newsroom

See what's new and what's trending from ERS.

ERS provides information on a range of farm labor issues, including:

Finally, we provide links to key data sources with summaries.

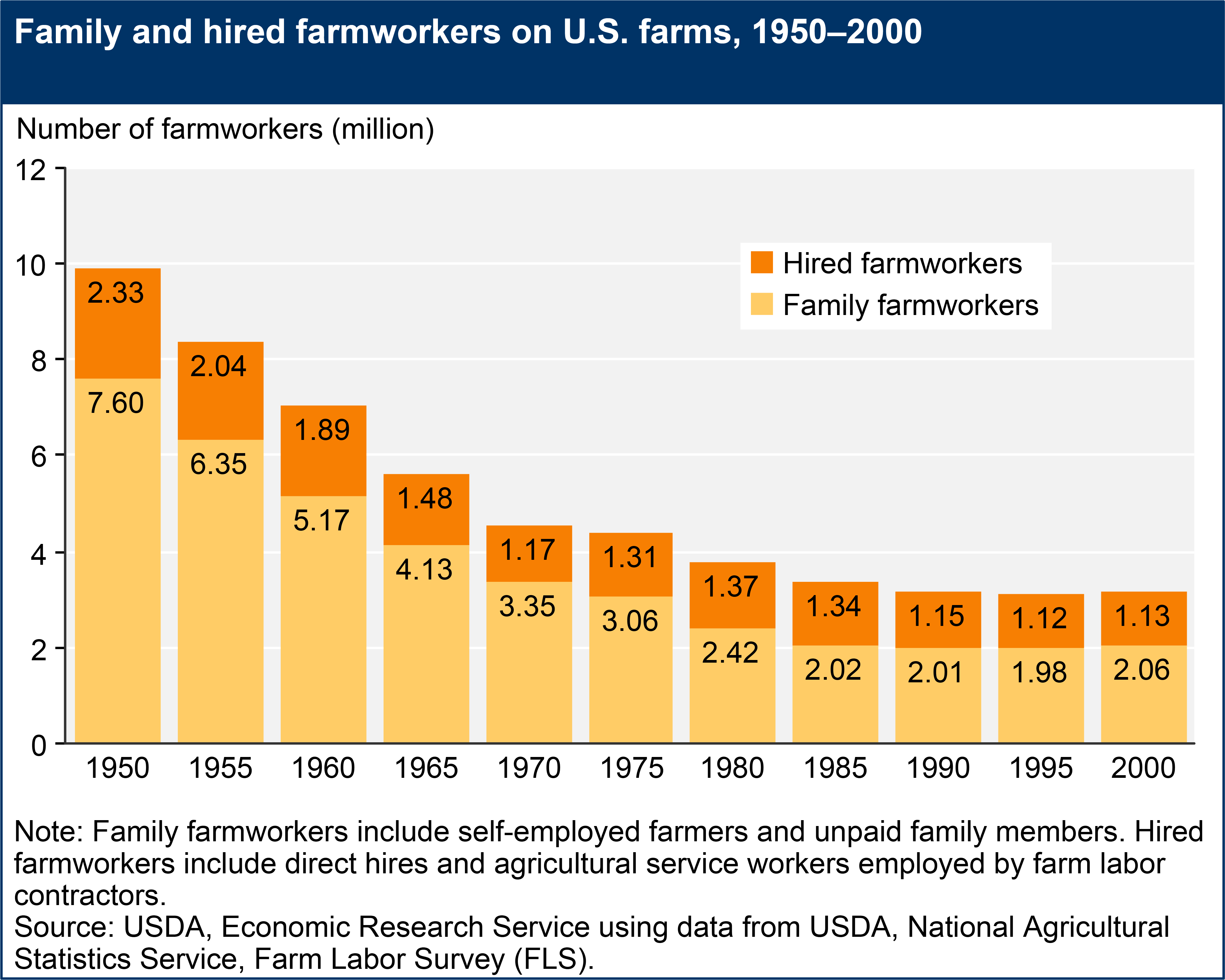

The U.S. agricultural workforce has long consisted of a mixture of two groups of workers: (1) self-employed farm operators and their family members, and (2) hired workers. Both types of employment were in long-term decline from 1950 to 1990, as mechanization contributed to rising agricultural productivity, reducing the need for labor. Since 1990, employment levels have stabilized.

The reduction in self-employed and family labor through 1990 was more rapid than the decline in hired labor. According to data from the Farm Labor Survey (FLS) of USDA’s National Agricultural Statistical Service (NASS), the number of self-employed and family farmworkers declined from 7.60 million in 1950 to 2.01 million in 1990, a 74-percent reduction. Over this same period, average annual employment of hired farmworkers—including on-farm support personnel and those who work for farm labor contractors—declined from 2.33 million to 1.15 million, a 51-percent reduction. As a result, the proportion of hired workers has increased over time.

Download chart image | Chart data

Download chart image | Chart data

The rest of this page describes the employment, earnings, demographic characteristics, and other information for the hired farm labor force only. (Information on the well-being of the self-employed farmers and their families may be found on the ERS topic page on Farm Household Well-being.)

Hired farmworkers make up less than 1 percent of all U.S. wage and salary workers, but they play an essential role in U.S. agriculture. According to data from the 2022 Census of Agriculture, wages and salaries plus contract labor costs represented just 12 percent of production expenses for all farms, but 42 percent for greenhouse and nursery operations and 40 percent for fruit and tree nut operations.”

Hired farmworkers are found in a variety of occupations, including field crop workers, nursery workers, livestock workers, graders and sorters, agricultural inspectors, supervisors, and hired farm managers. The majority are wage and salary workers, hired directly by farmers, but some are employees of agricultural service companies, including farm labor contractors, custom harvest providers, and management service providers. Many industrywide employment estimates also include support personnel on farms, such as human resource managers, sales agents, and truck drivers.

Many hired farmworkers are foreign-born people from Mexico and countries in Central America, with many lacking authorization to work legally in the United States. In recent years, farmworkers have become more settled, fewer migrating long distances from home to work, and fewer pursuing seasonal follow-the-crop migration. The number of young, recent immigrants working in agriculture has also fallen, and as a result the farm workforce is aging. Over the past 30 years, wages for hired farmworkers have gradually risen, both in real terms and in relation to wages for the average nonsupervisory worker in a nonfarm occupation.

Hired farmworkers are employed in both metro (urban) and nonmetro (rural) counties. The statistics presented here refer to farmworkers nationwide, unless otherwise indicated.

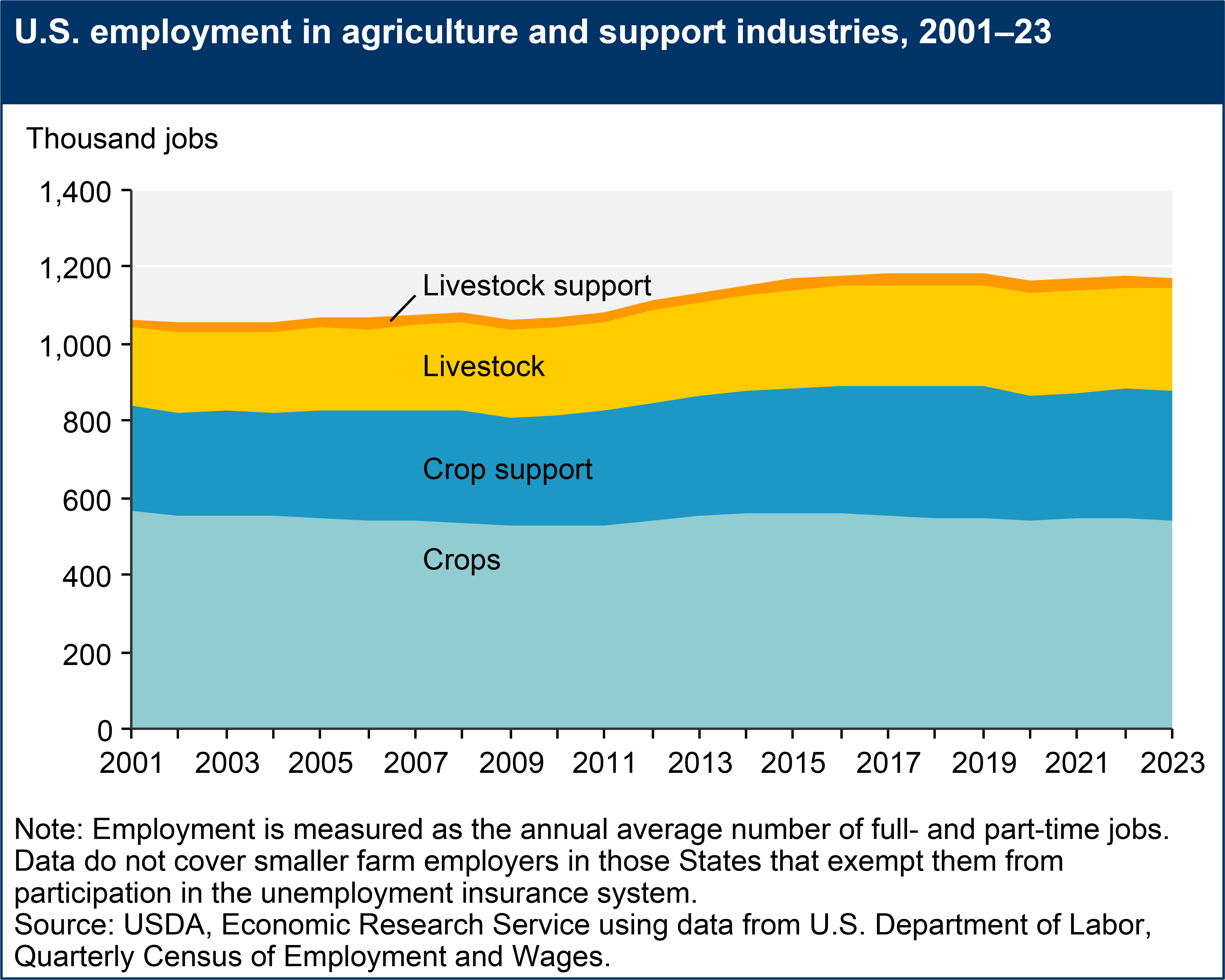

According to data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), wage and salary employment in agriculture (measured as the annual average number of full- and part-time jobs)—including support industries such as farm labor contracting—stabilized in the 2000s and has been on a gradual upward trend since 2010, rising from 1.13 million in 2013 to 1.17 million in 2023, a gain of 4 percent.

From 2013 to 2023, employment increases were highest in crop support services (which added about 17,400 jobs, a 6-percent increase) and the livestock sector (which added about 29,000 jobs, a 12-percent increase). It should be noted that the QCEW is based on unemployment insurance records, not on surveys of farms or households. As a result, it does not cover smaller farm employers in those States that exempt such employers from participation in the unemployment insurance system.

However, survey data sources, such as the American Community Survey and the Current Population Survey, also find rising farm employment since the turn of the century.

Download chart image | Chart data

Download chart image | Chart data

Demographic information on farmworkers can be found in the American Community Survey (ACS) from the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. These data also allow us to distinguish among manual laborers, managers/supervisors, and other occupations in the industry. Farm laborers have lower levels of educational attainment, are slightly younger than U.S. private wage and salary workers, are more likely to be Hispanic of Mexican origin, and are less likely to be citizens than both workers in other occupations in agriculture and the U.S. wage and salary workforce as a whole.

Differences in demographics are also evident between crop and livestock workers (not shown in table). A larger share of laborers in crops and related support industries are female (28 percent versus 20 percent in livestock). Crop laborers are also less likely to be non-Hispanic White (26 percent versus 49 percent for livestock), and less likely to have been born in the United States (41 percent for crop workers in manual labor occupations versus 65 percent for manual livestock workers). Finally, crop laborers have lower levels of educational attainment: 47 percent lack a high school degree, compared with 34 percent in livestock.

Notably, the U.S. Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS), discussed below, finds larger shares of foreign-born, Hispanic, and less-educated employees among crop and support workers than does the ACS (livestock workers are not surveyed in NAWS). For example, according to NAWS estimates from data spanning fiscal years 2020–22, just 32 percent of crop farm workers in manual labor occupations were U.S. born, compared with 41 percent in the 2022 ACS.

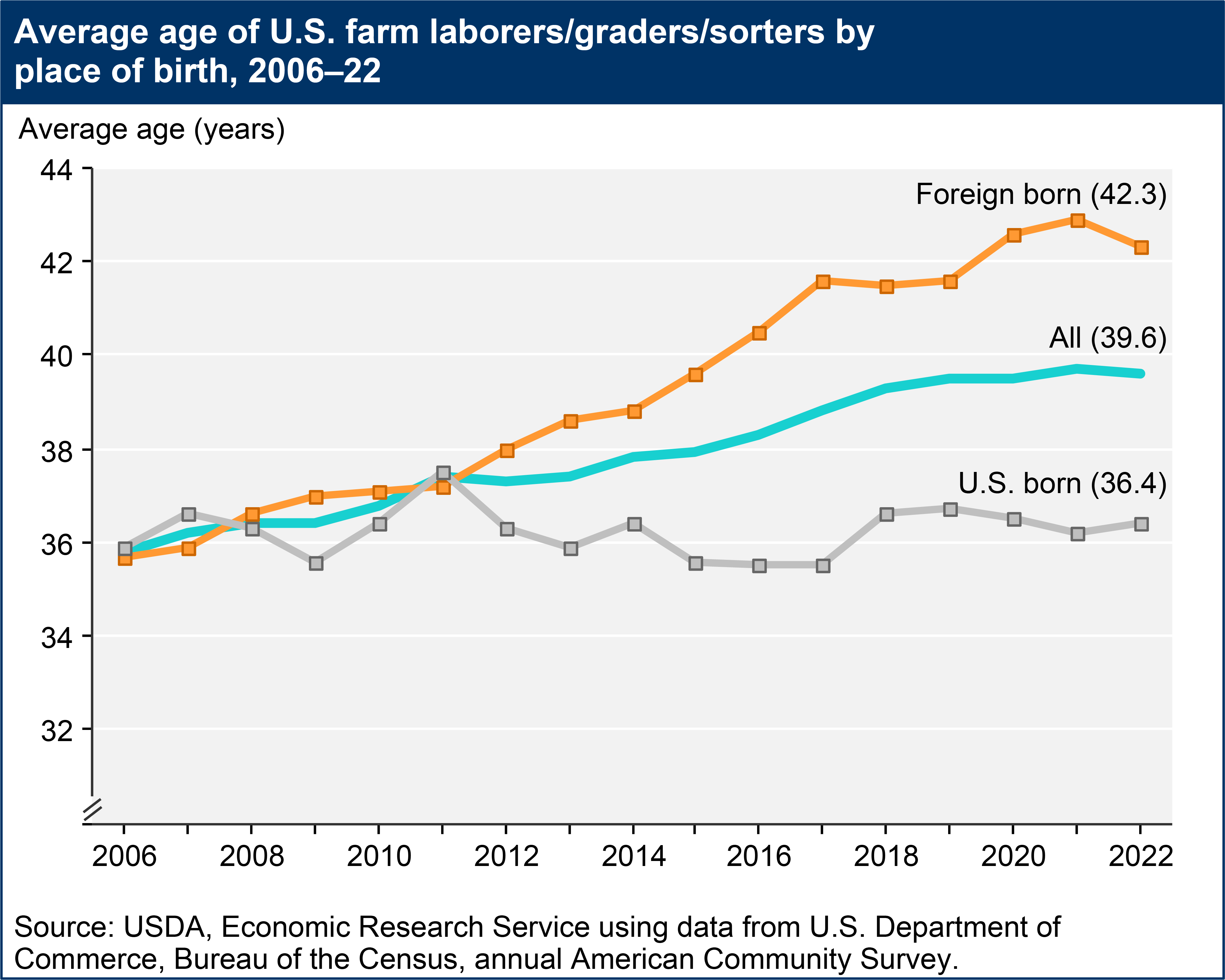

As fewer young immigrants are entering agriculture, the average age of foreign-born farmworkers has risen, pulling up the average for the farm workforce as a whole.

The average age of foreign-born farmworkers rose by close to 7 years between 2006 and 2022. In contrast, the average age for U.S.-born farmworkers has remained roughly constant over this period.

Download chart image | Chart data

Download chart image | Chart data

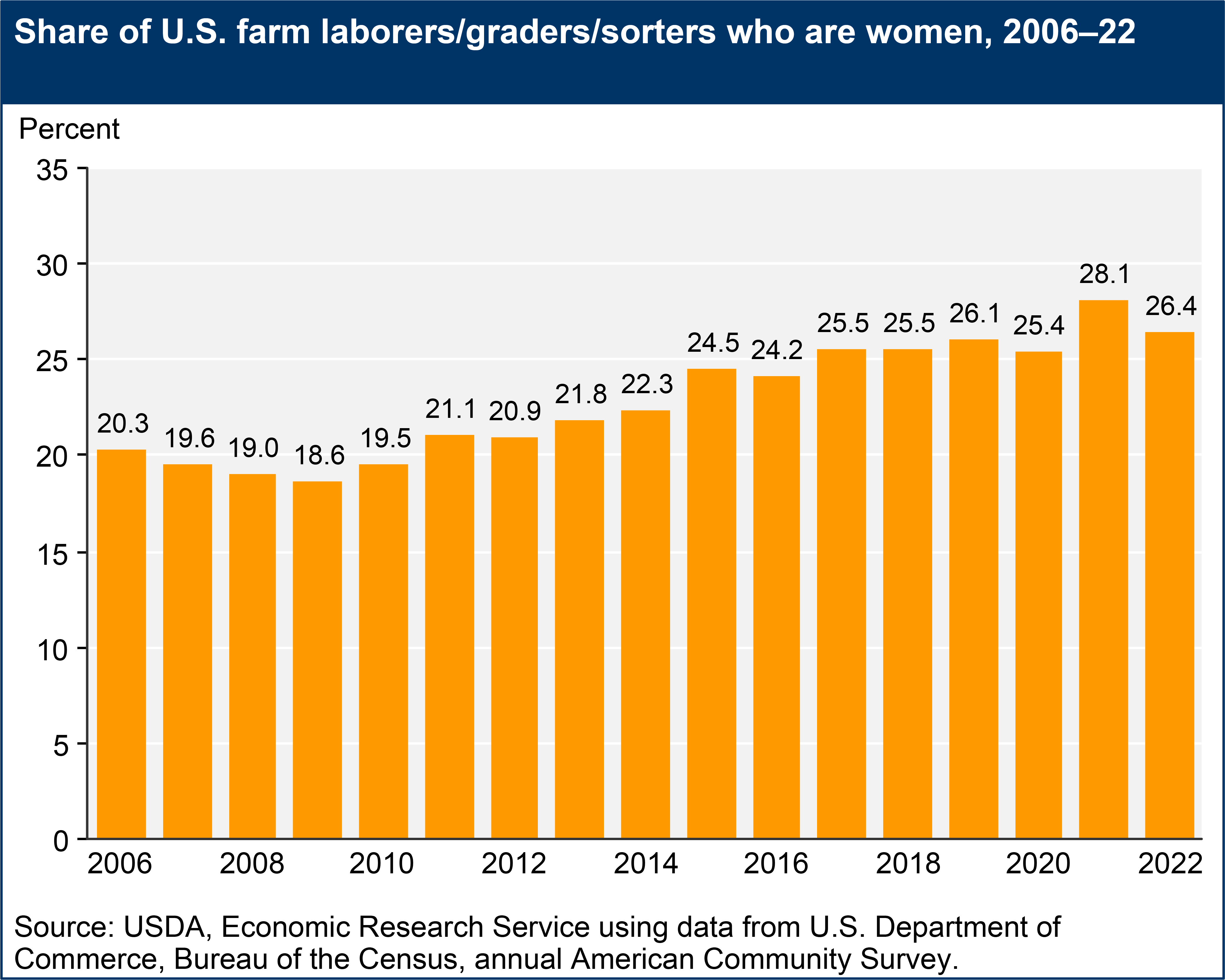

The share of farmworkers who are women declined in 2006–09, from 20.3 percent to 18.6 percent, but has since climbed to 26.4 percent (in 2022). The fact that the female share fell during the Great Recession and has risen during the recovery is consistent with men moving into agriculture as employment in the nonfarm economy declines, and out of agriculture as nonfarm job prospects improve. The rising female share is also consistent with the fact that, as labor costs rise, some growers are adopting mechanical aids (such as hydraulic platforms that replace ladders in tree-fruit harvesting, and mobile conveyor belts that reduce the distance heavy loads must be carried) which facilitate more women and older workers in performing tasks that traditionally have been performed by younger men.

Download chart image | Chart data

Download chart image | Chart data

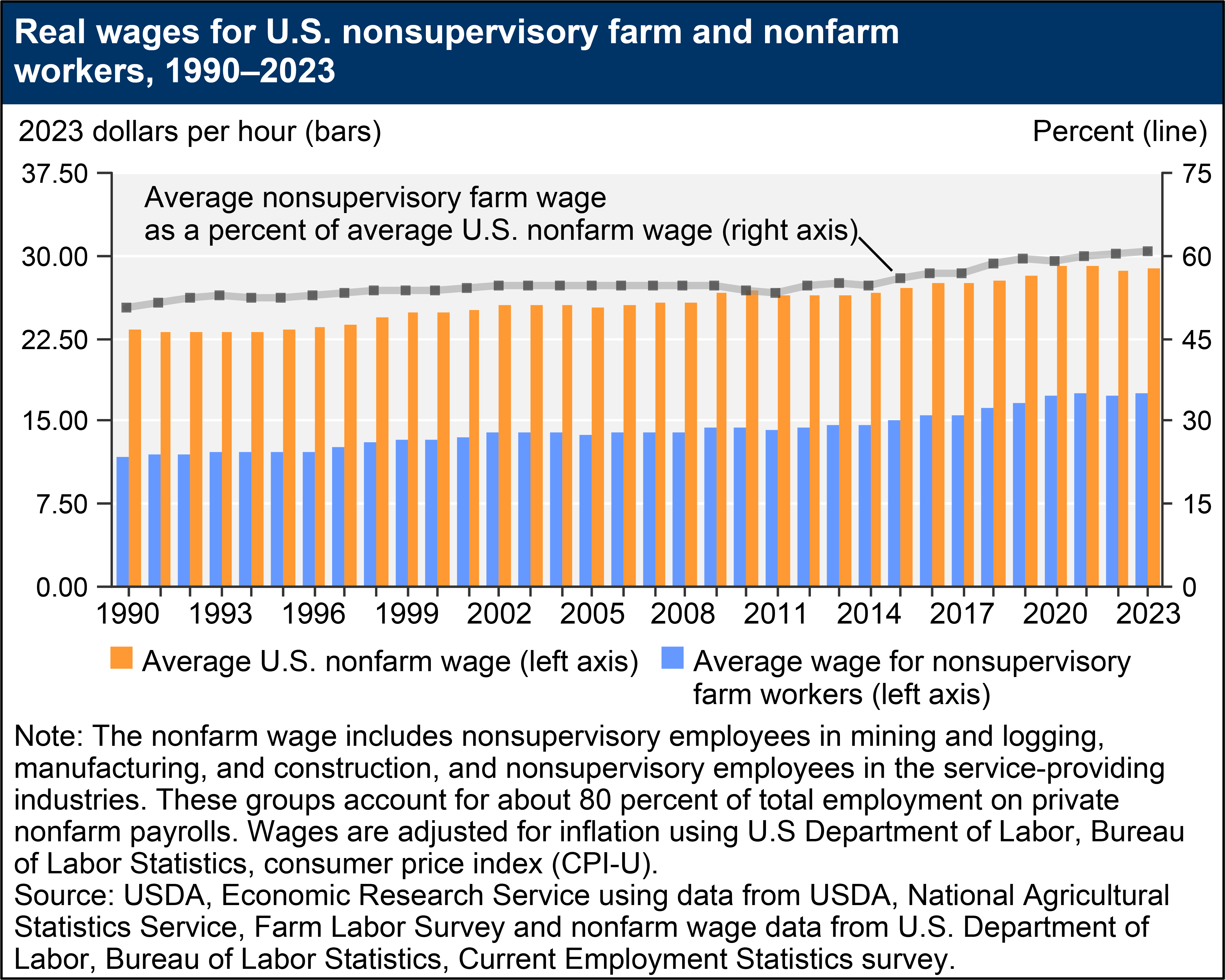

According to data from the FLS, real (inflation-adjusted) wages for nonsupervisory crop and livestock workers (excluding contract labor) rose at an average annual rate of 1.1 percent per year between 1990 and 2023. In the past 5 years, however, real farm wages grew at 2.1 percent per year, consistent with growers’ reports that workers were harder than usual to find.

In 1990, the average real farm wage for nonsupervisory crop and livestock workers was just over half the average real wage in the nonfarm economy for private-sector nonsupervisory occupations ($11.71 versus $23.19, in 2023 dollars). By 2023, the farm wage ($17.55) was equal to 61 percent of the nonfarm wage ($28.93). In other words, the gap between farm and nonfarm wages is slowly shrinking, but still substantial.

Download chart image | Chart data

Download chart image | Chart data

Wages for nonsupervisory occupations varied little across occupations, ranging from $16.36 (for packers and packagers) to $18.47 (for equipment operators). For five out of the six nonsupervisory occupations, however, wages were more than 3.5 percent higher in 2023 than in 2022 (not adjusted for inflation).

Average hourly wages for hired agricultural managers stood at $28.79 in 2023, up 4.4 percent from the year before. Supervisor wages averaged $25.61 per hour, up 6.4 percent from 2022 (not adjusted for inflation).

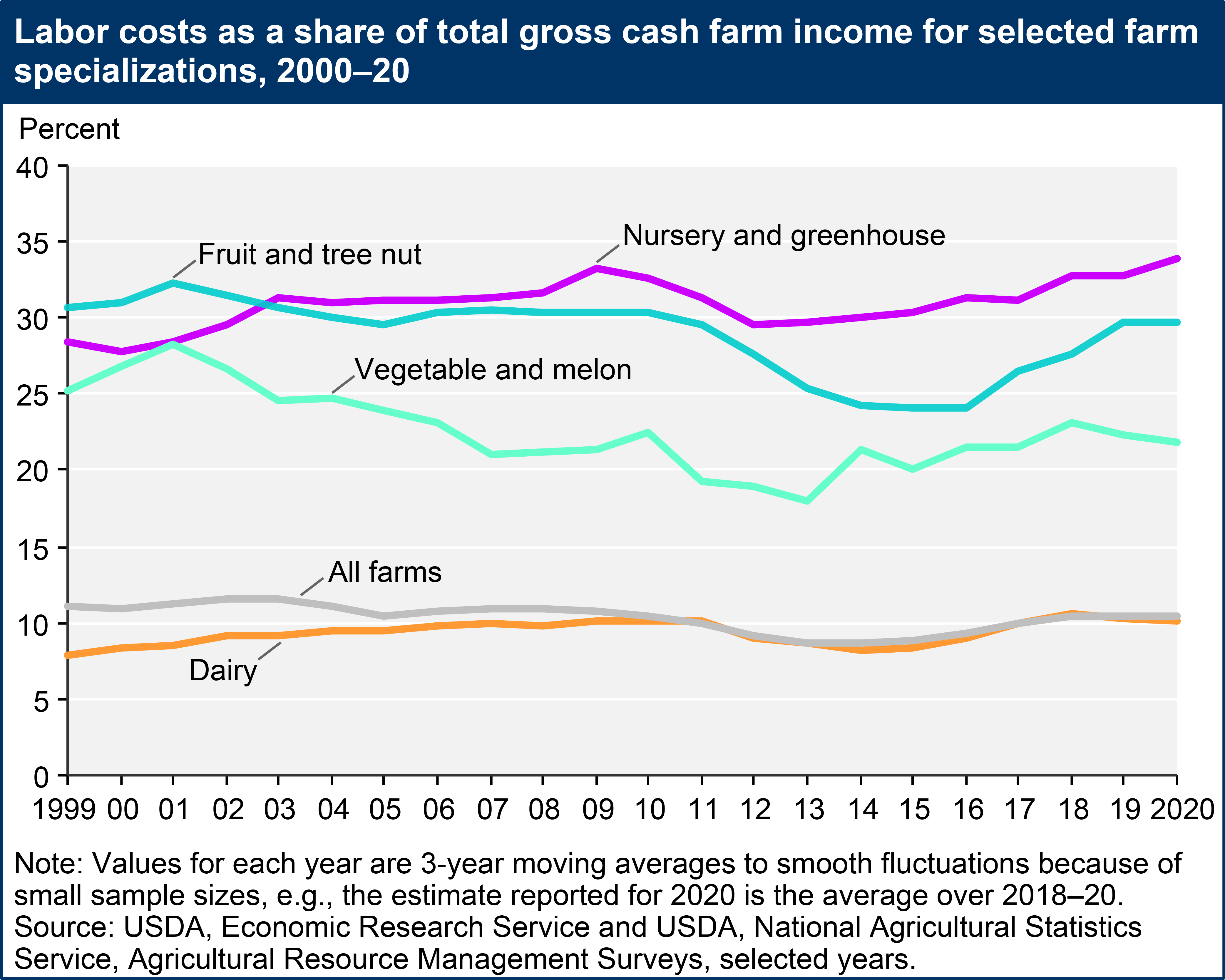

Although farm wages are rising in nominal and real terms, the impact of these rising costs on farmers’ incomes has been offset by rising productivity and/or output prices. As a result, labor costs as a share of gross cash income do not show an upward trend for the industry as a whole over the past 20 years. For all farms, labor costs (including contract labor, and cash fringe benefit costs) averaged 10.4 percent of gross cash income during 2018–20, compared with 11.0 percent during 1998–2000.

However, these trends in labor cost shares differ by commodity. Labor cost shares have fallen slightly over the past 20 years for the more labor-intensive fruit and vegetable sectors, although they appear to have been trending upwards again in the past few years. On dairies and in nursery operations, both of which also rely heavily on immigrant labor, labor costs as a share of income are at or near their 20-year highs.

Download chart image | Chart data

Download chart image | Chart data

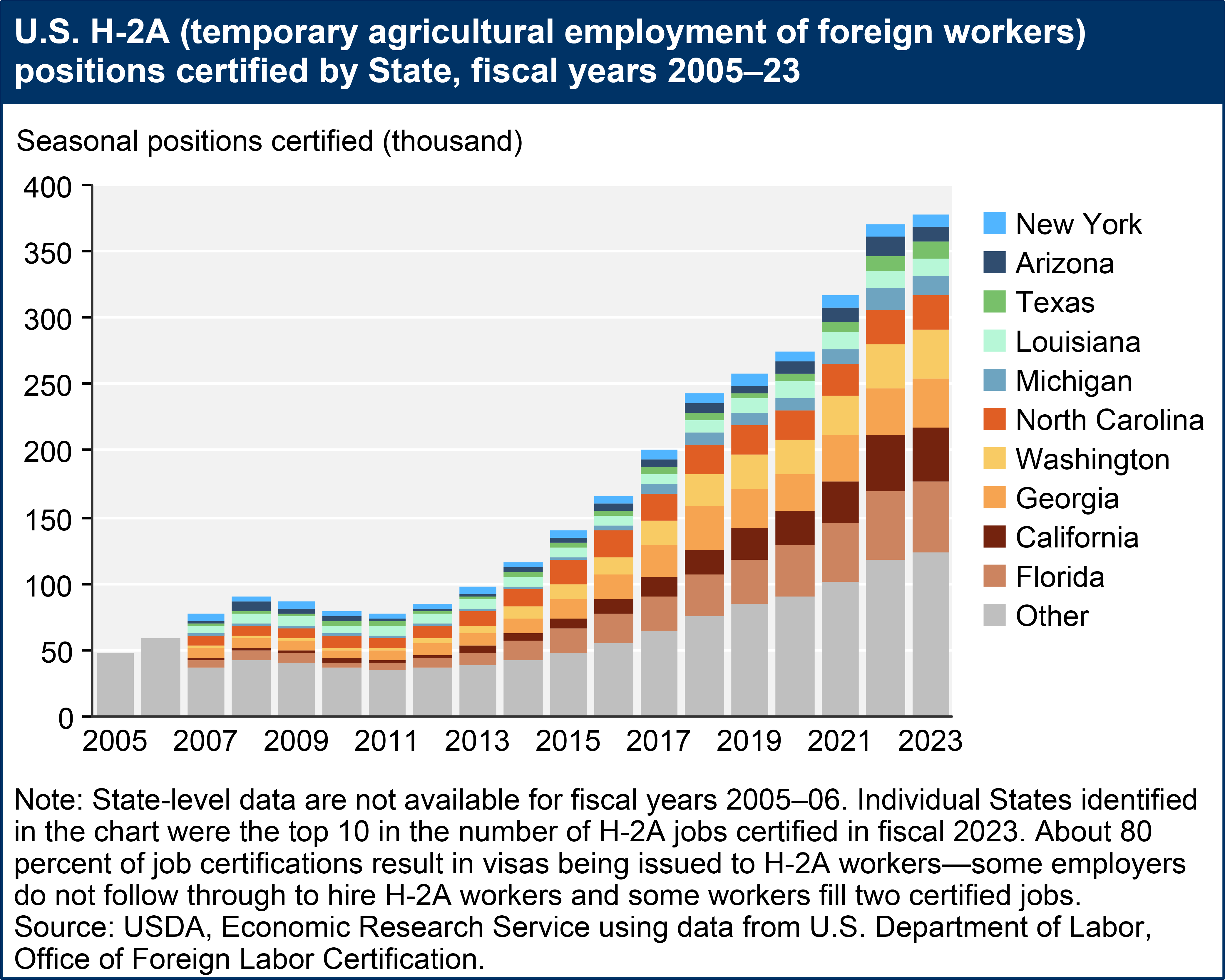

The H-2A Temporary Agricultural Program—often called the H-2A visa program—provides a legal means to bring foreign-born workers to the United States to perform seasonal farm labor on a temporary basis, for a period of up to 10 months. Crop farmers can use this program to meet their seasonal labor needs, but most livestock producers, such as ranches, dairies, and hog and poultry operations, are not legally allowed to use the program to meet year-round labor needs. An exception to this restriction is made for producers of livestock on the range, such as sheep and goat operations, who can use H-2A workers year-round.

Employers in the H-2A program must demonstrate, and the U.S. Department of Labor must certify, that efforts to recruit U.S. workers were not successful.

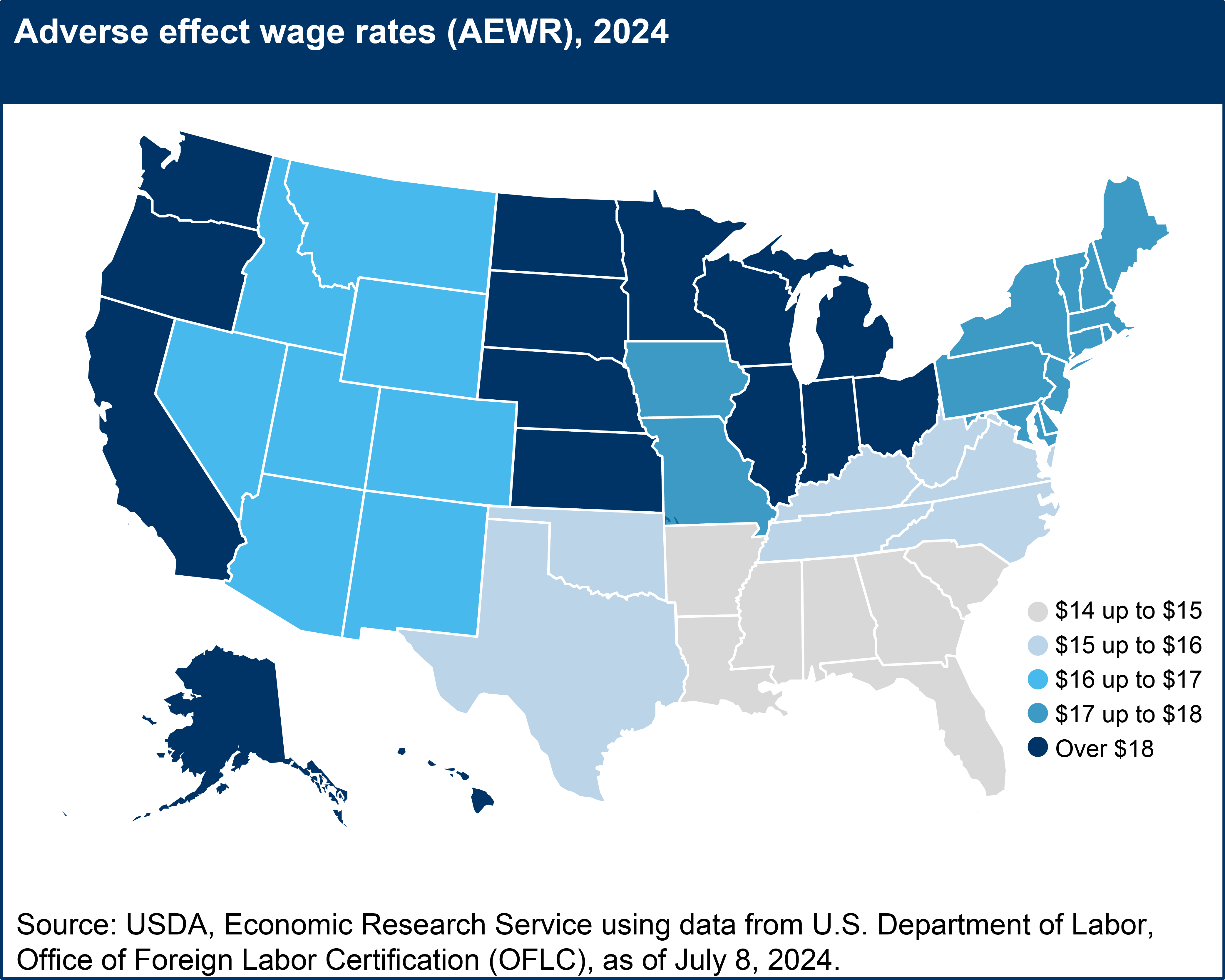

Employers must also pay a State-specific minimum wage, which may not be lower than the average wage for crop and livestock workers surveyed in the FLS in that region in the prior year, known as the Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR). (See the next section for details on the AEWR.) In addition, employers must provide housing for their H-2A workers and pay for their domestic and international transportation.

One of the clearest indicators of the scarcity of farm labor is the fact that the number of H-2A positions requested and approved has increased more than sevenfold in the past 18 years, from just over 48,000 positions certified in fiscal 2005 to around 378,034 in fiscal year 2023. The average duration of an H-2A certification in fiscal 2023 was 5.75 months, implying that the 378,034 positions certified represented around 180,000 full-year equivalents. A certified job does not necessarily result in the issuance of a visa; in fact, in recent years only about 80 percent of jobs certified as H-2A have resulted in visas. Around 310,000 visas were issued in fiscal 2023 by the Department of State.

Download chart image | Chart data

Download chart image | Chart data

H-2A employers must provide transportation and housing and pay the higher of the applicable State or federal minimum wage, the prevailing wage in that region and occupation, as determined by the U.S. Department of Labor, or the regional average farm wage observed in the NASS FLS. The latter is known as the Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR), reflecting the legal requirement that H-2A employment should not negatively affect domestic farmworkers by lowering the average wage. For fiscal 2024, this minimum hourly wage ranged from $14.53 (in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi) to $19.75 (in California) and $20.72 (in the District of Columbia).

Download chart image | Chart data

Download chart image | Chart data

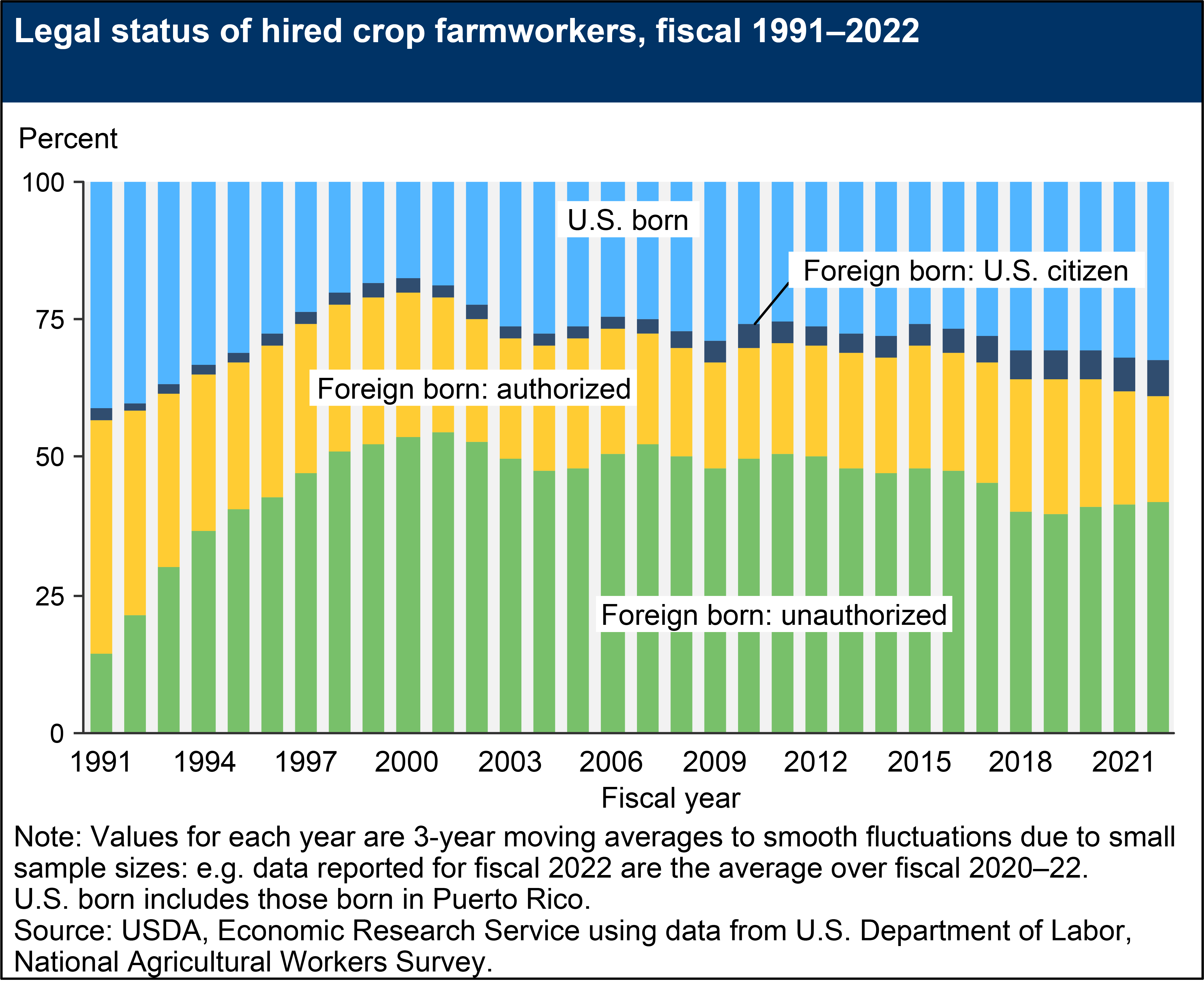

Legal immigration status is difficult to measure: not many surveys ask the question, and unauthorized respondents may be reluctant to answer truthfully if asked. The U.S. Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) provides data on farmworkers’ legal immigration status. NAWS data, believed to be of high quality, is gathered by trained and trusted enumerators who conduct face-to-face interviews with workers at their job sites and with their employers’ permission. NAWS also queries workers on their inter- and intranational migration patterns. One limitation of the NAWS, however, is that it excludes the growing number of H- 2A workers, as well as all hired livestock workers.

The share of hired crop farmworkers who were not legally authorized to work in the United States grew from roughly 14 percent in 1989–91 to almost 55 percent in 1999–2001; in recent years it has declined to about 40 percent. In 2020–22, 32 percent of crop farmworkers were U.S. born, 7 percent were immigrants who had obtained U.S. citizenship, 19 percent were other authorized immigrants (primarily permanent residents or green-card holders), and the remaining 42 percent held no work authorization. The share of workers who are U.S. born is highest in the Midwest, while the share who are unauthorized is highest in California.

Download chart image | Chart data

Download chart image | Chart data

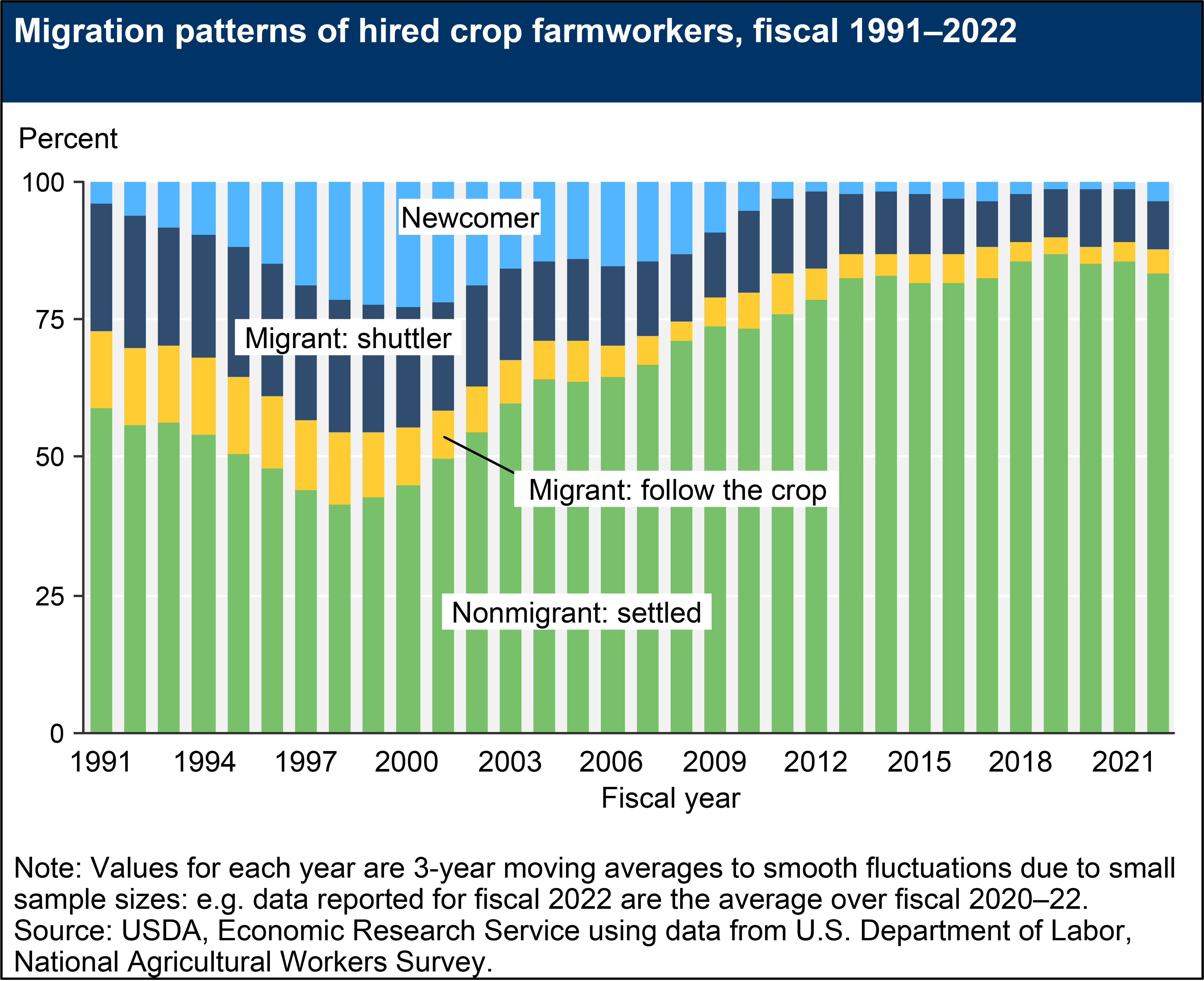

Eighty three percent of hired crop farmworkers are not migrant workers but are considered settled, meaning that they work at a single location within 75 miles of their home. This share is up from 41 percent in 1996–98, reflecting a profound change in the nature of the crop farm workforce.

Among the small share of remaining migrant workers, the largest group is “shuttlers,” who work at a single farm location more than 75 miles from home and may cross an international border to get to their worksite. Shuttlers made up about 9 percent of hired crop farmworkers in 2022, down from about 24 percent in 1996–98.

More common in the past, the “follow the crop” migrant farmworker, who moves from State to State working on different crops as the seasons advance, is now a relative rarity. These workers made up just 4 percent of those surveyed by the NAWS in 2020–22, down from a high of 14 percent in 1992–94.

The final category of hired crop farmworkers is newcomers to farming, whose migration patterns have not yet been established. The fact that they now represent just 3.6 percent of the crop farm workforce, down from as much as 22 percent in 1998–2000, in part reflecting the slowdown in net migration from Mexico to the United States since 2007.

Download chart image | Chart data

Download chart image | Chart data

2/6/2025

1/8/2025

1/5/2025

1/28/2025

10/8/2024

8/27/2024

Economic Research Service