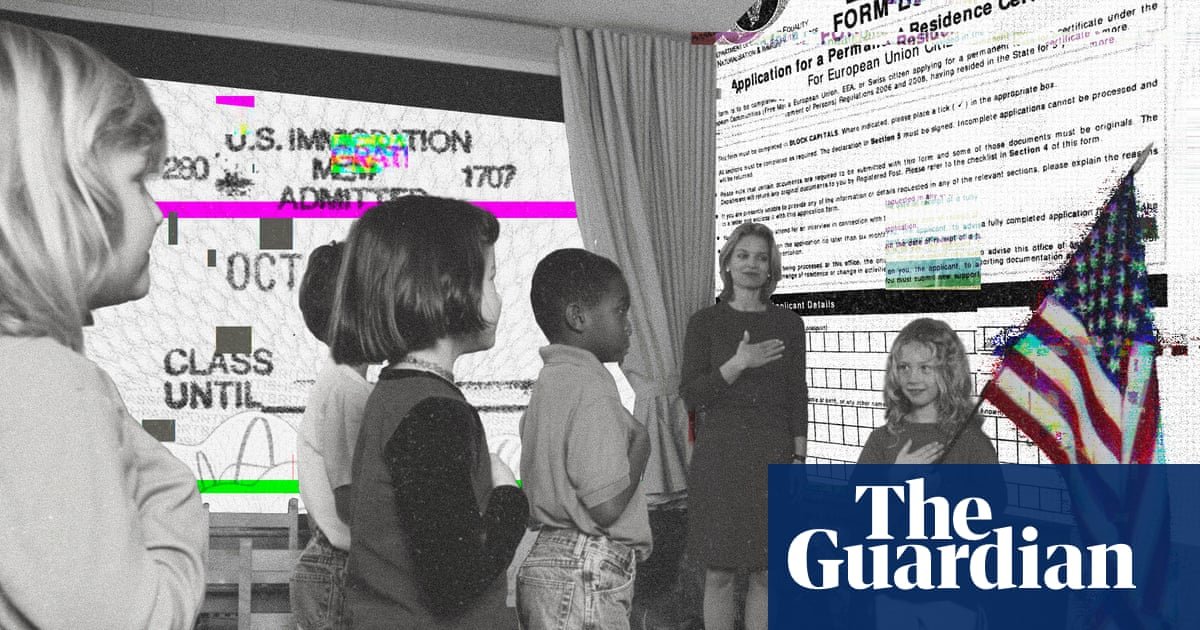

Since Trump’s immigration crackdown, global perceptions of America have plummeted. Citizens and non-citizens alike are rethinking whether we still want US passports

It starts with a quiz from a law firm: did your grandparents leave before or after 1951? Do you have their passports or marriage certificate?

If I answer correctly, I will get another email from a lawyer who specializes in citizenship claims. If I do not, my file may be quietly marked as a long shot. The stakes are high: if successful, I could ultimately obtain an EU citizenship for myself and then perhaps for other members of my family.

Like many other Americans, I began this process in a moment of disillusionment. Since the 2024 election, I have been living with what I have come to call “citizenship insecurity”, a new category of instability that millions of us are now grappling with. It is the unsettling sense that a US passport, once a symbol of safety and mobility, is no longer something we identify with.

I am not living in fear of Ice raids; I am privileged enough to be a US citizen. I am not applying for another passport out of immediate danger or fear. Instead, it is about estrangement: I no longer recognize my country’s values.

Since the US’s inception, Americans have told ourselves a story about who we are and what we represent. We knew we were not perfect, but we thought America at least pretended to try to stand up for democracy and human rights. Much of that story has been tossed aside in the last decade, along with the dismantlement of our social contracts. “Citizenship insecurity” captures the depth of that unraveling, not necessarily imminent danger but no longer recognizing America, or trusting its values.

“My anxiety is through the roof right now, but I think it would be worse if I were not a citizen,” says Juan M Hincapie-Castillo, a researcher at the University of North Carolina and a recently naturalized American who first came to this country as an international student.

He is experiencing citizenship insecurity to the max. “I am still brown, queer, and have an accent. I have tattoos that I cover every time I travel and go through TSA,” he says. “I keep hearing stories of legal residents and citizens being detained.”

The instability Hincapie-Castillo experiences is a more targeted and virulent form than what I am experiencing. Right now, just being queer or brown – or even simply having tattoos, given the outsized role those have played in the recent roundups of alleged immigrant gang members – can seem to make a person more vulnerable to being singled out.

Just this month, Hincapie-Castillo’s medical research on pain management treatments was defunded by the Trump administration. He studies trigeminal neuralgia, a facial nerve condition that is so cruel it is sometimes referred to as a “suicide disease”.

His work had been funded for five years by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), but the grant was terminated after only one year. The stated reason for termination: a new NIH policy declaring that research programs connected to diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) are “antithetical to scientific inquiry”. (Some demographics’ pain no longer counts to those in power, apparently.)

Indeed, this is another part of citizenship insecurity today: the economic pressures on scholars as federal funding has been haphazardly cut in the sciences and other disciplines. A number of these academics are internationally born, which adds an additional layer of uncertainty.

“The fear is always there,” he says of his current life. “I carry my US passport now everywhere I go, just in case.”

Of course, the woes of American citizens experiencing insecurity like Hincapie-Castillo do not even compare to the threat against non-citizens: it is as if many of us are nesting dolls of uncertainty.

By 1 June, 51,302 people were in Ice detention. As of 13 July , the number had ticked up to 56,816. The Ice site has not shared numbers for deportations in 2025 publicly yet. The current head of Ice apparently told an Arizona Mirror reporter that our deportation system needs to be more like “Amazon Prime, but with human beings”. He meant that as a good thing.

And yet, the fear American citizens who are in far less outright peril also feel is still real. Recently, Donald Trump threatened to withdraw the actor Rosie O’Donnell’s citizenship. Petulant as his threat was, it nonetheless showed that the president would like to denaturalize even native-born people who he reviles. The threat to birthright citizenship speaks to that same issue.

Citizenship insecurity is about grappling with what it means to be American when so many of our supposed ideals have vanished – not just from policy, but from political discourse itself.

This is not the first time Americans have lived alongside wars or policies they did not support. For decades, many of us have witnessed enormous political endeavors we did not approve of, from the war in Iraq to the war in Vietnam. This included the “forever wars”, which were attacks on much we valued about our country, all at once, but it also included phenomena that presage and accompany those wars: torture, military occupation and Islamophobia at home.

As a journalist focused on income inequality and economic insecurity, I did not buy into the “American dream” mythos. Editing big stories about economic inequality in this country day in, day out, I have been shown over and over that the notion of pulling yourself by your bootstraps is a fantasy. I have interviewed people who did everything “right” – saving money, pursuing higher education, working 40 hours a week – and still live from paycheck to paycheck, unable to buy a home or to even recognize a clear life trajectory.

Nonetheless, a small part of myself held on to an idea of America as a beacon of sorts, as it had been for my immigrant grandparents.

My grandfather left a town that has been controlled by different countries in eastern Europe for the US in 1929, returned to marry my grandmother, and together they came back again in the early 1930s. But most of our family did not make it out. They died there: Jews caught in a hideous historical fulcrum, crushed by the machinery of genocide and occupation.

As a result, my grandparents loathed talking about the past and what happened there, preferring to pass it over in silence. What would they think of the choice that I and others were hoping to make now?

America had offered them a chance to own their own store and for their children to go to college; my mother even made it to the Ivy League on scholarship. It was not a country I ever wanted to have an opportunity to leave or thought I or my family might need one.

That has changed – for me and others.

Nadia Kaneva, for example, is a media and communications professor at the University of Denver who has spent years studying how nations brand themselves. Born in Bulgaria and only recently naturalized as an American, Kaneva is feeling citizenship insecurity in real time.

As a scholar, she has long understood how a country that is no longer desirable to emigrate to affects and is affected by foreign investment, tourism and brain drain. In the US, symbolic security has started to erode and other countries are jumping on the opportunities. A few European universities, for instance, have announced programs to recruit American researchers to Europe, especially if they are, say, public health scholars or environmental studies specialists or sociologists concentrating on gender.

Kazim Ali, a co-founder of Nightboat Books and the author of the book Resident Alien, feels that the challenge to his and others’ identities as Americans is “existential as well as direct”. He emigrated here with his parents, who were Muslims born in India (“So India doesn’t feel like home, either, at the moment,” he says).

Would he ever consider leaving? To this, he quotes the Uruguayan poet Cristina Peri Rossi, who once said of her condition of exile and return: “I don’t want to trade one nostalgia for another.”

It is not only longtime citizens who are rethinking what it means to be American. Even those newly eligible for citizenship – people who once looked forward to formally pledging allegiance – are now pausing.

Those people “have told me they are now torn”, says Michele Wucker, a risk governance expert who also has written extensively about citizenship. “The actions of this administration do not align with the country they thought we were. And now they question the logic of becoming a citizen out of fear of how Maga believes we should treat non-citizens.”

Of course, some argue that seeking out the insurance of a second passport or planning to escape to a university job in another country is weak-hearted – that we must stay and fight for the democracy we want to live in. Others decry running away as unpatriotic, as when scholars of authoritarianism at Yale – Timothy Snyder, Jason Stanley and Marci Shore – announced publicly that they were moving to Canada for academic positions.

In response, the scholar Siva Vaidhyanathan wrote that we should seek ballast from the writer James Baldwin’s “unromantic patriotism” in these times and “stay, fight, and to urge others to as well.”

I see his and other writers’ point: given my own relatively privileged position, I would never leave this country unless I really felt I had to.

I interviewed a Jewish faith leader who is originally from Israel, has an American passport but is also in the middle of obtaining her Portuguese citizenship (she is Sephardic, meaning her ancestors are from the Iberian peninsula). She wants to remain anonymous in part to protect her child, who is transgender, and expanding her options for citizenship feels more urgent than ever. She is also applying, she says, because the current American political situation plays “into centuries-old insecurity of the Jewish people”. For her, citizenship insecurity has been compounded by what she calls “the state of violence of the country [Israel] I come from”. The sense of instability is not confined to one place – it echoes across borders. It is not just about mobility or paperwork – it is about protection, about having somewhere for her child to go if things get worse.

Melissa Aronczyk, a media studies professor at Rutgers University and author of Branding the Nation: the Global Business of National Identity, comes from Canada. She has been thinking of returning home “incessantly” since January. “There is a cabal of Canadians in the US where that’s a central topic right now,” she says. In conversations in a Facebook group for her fellow expats living in the US, trying to get their kids into Canadian universities has become a far more insistent theme as of late. “Canadian American parents getting their kids to apply to Canadian rather than American universities was once a tuition move,” says Aronczyk. Now, she says it’s also political as well.

Aronczyk, like many of the people I spoke to, is quick to acknowledge her relative privilege. We know we are lucky, even, in being able to consider second citizenships. But that is precisely the point: when even the relatively economically secure feel as if the ground shifts beneath them, it signals just how deep and wide this instability runs.

As an expert on national branding, Aronczyk notes that the US’s image has sharply deteriorated in the past six months. Since the start of Trump’s second administration, global perceptions of America “have gone negative, by almost every measure”.

A national brand is defined as much by people with American passports as people watching our country from the outside: students, tourists and investors, she points out.

In June, I started my regular correspondence with a law firm representing people seeking European citizenship. Each time I wrote and heard back from them, I recalled my beloved grandfather.

In one old photo, he wore his cavalry uniform, adorned with sparking buttons. I remember that handsome expression from my childhood in the 1970s when he was already an old man, still attractive and bewildered. Whether that was due to his feeling caught in the gears of history or not it was hard to say.

What I do know was he was eager to be the sort of American who took his kids to movie palaces and had college money tucked away for their grandchildren, no matter that he and grandma worked six days a week in a shoe store to be able to do so. In his old age, he got to watch Star Trek with his feet up as the two ate strawberry ice-cream. Occasionally, once retired, my grandmother would even attend outdoor classical concerts and free Shakespeare plays with her friends. This, to them, was the American dream.

It still strikes me as uncanny, to even be considering giving myself and my family the possibility to go elsewhere if the worst happens here. After all, this country was my grandparents’ refuge. But I imagine they would understand, and even approve. They knew all too well the cost of having the wrong citizenship at the wrong time.

I don’t identify with my country’s values anymore. Is this ‘citizenship insecurity’? – The Guardian