Support non-profit journalism and perspectives from around the world.

See all those languages? The Lingua project at Global Voices works to bring down barriers to understanding through translation.

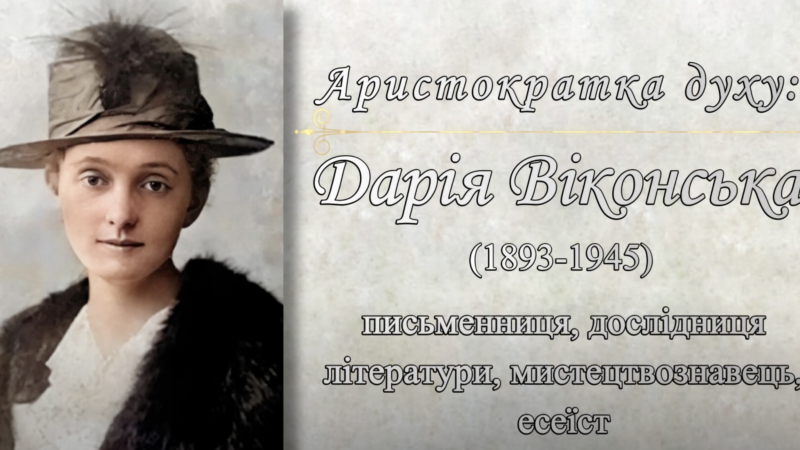

Portrait of Daria Vikonska. Screenshot of YouTube Channel Запорожская ОУНБ. Fair use.

By Julia Stakhivska

This story is part of a series of essays written by Ukrainian artists entitled “Regained Culture: Ukrainian voices curate Ukrainian culture.” This series is produced in collaboration with the Folkowisko Association/Rozstaje.art, thanks to co-financing by the governments of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia through a grant by the International Visegrad Fund. The mission of the fund is to advance ideas for sustainable regional cooperation in Central Europe. It has been translated from Ukrainian by Iryna Tiper and Filip Noubel.

“Simply to go somewhere far away and see if there are still paradise islands in the world.” This is how writer Sofia Yablonska described her desire to travel in an interview for the Lviv Ukrainian-language magazine “Nazustrich” in 1935. The travelogues of Sofia Yablonska, Daria Vikonska, and Olena Kysilevska have shaped women’s emancipation and literature in Western Ukraine, then part of Poland.

This Ukrainian woman traveled around the world with a camera, wrote travelogues about Morocco, East Asia, Australia, and Oceania. If she were alive today, she would probably have millions of followers on social networks. But a century ago, a woman traveler looked even more exotic.

The traveller Sofia Yablonska as painted by artist Tanya Kornienko. Screenshot from her YouTube channel Tanya.

Sofia Yablonska was born on May 15, 1907, near Lviv to a priest father. She studied at the teachers’ seminary and enrolled in acting and business courses for women. Her dream of becoming a film actress took her to Paris in 1927, where she studied the techniques of documentary photography and cinema. After a few years, she penned the book “The Charm of Morocco” (1932): a story about exoticism where she describes everyday life, fire-eaters, viper-eaters, harems, chess games with a local nobleman-kaida, expeditions to the land of the Berbers, and “Europeanization,” mockery of tourists who trust guidebooks more than their own eyes.

In her writing, Yablonska is enchanted and enchants: “Having reached the edge of the oasis and looking from under the shadow of the last palm tree at the Sahara bathed in the fiery sun, you experience the same joyful impression as if you were looking at a fierce blizzard in winter through the window of a warm room.”

In December 1931, Yablonska signed a contract for documentary photo essays and set off on a trip around the world. In Port Said, she was surrounded by children eager to be filmed, in Djibouti, she was surprised with sunburn, in Ceylon, she talked to trees. In Laos, she hunted a tiger. In Cambodia, she pondered over Buddhism and suffered from malaria, in Thailand, she fled from the courtship of a prince, in Malaysia, she was treated by a medicine man, in Bali, she participated in rituals, and hunted a shark. On the island of Bora Bora, she was given the joyful name of Teura, “The Red Feather of Kings,” and in Tahiti, the place she longed for so much in her search of paradise islands, she listened to the revelations of Queen Marau: “The destiny of Tahiti is to die. Our astrologers have long predicted this end. […] And we should not be pitied. We are still, perhaps, the last happy people in the world. We have the sun, the warmth, our gardens are full of vegetables, the sea is full of fish, our souls are carefree!”

In 1939, Yablonska left her homeland forever and went to China, where she met her husband, the French businessman Jean Houdin. Together, they had three sons, the youngest, Jacques-Mirko Houdin, became a politician. Sofia Yablonska symbolically ended her earthly journey “on the road”: in a car accident on February 4, 1971, while taking the manuscript of a new book to her publishing house. She is buried on the French island of Noirmoutier.

Daria Vikonska is the pseudonym of Joanna Karolina Mayer-Fedorovych, known as Malytska once she married. She came from an ancient princely family, known since the times of medieval Kievan Rus. She was related to the Czech-Polish family of Naglik-Lozy de Lozenav. She was born on February 17, 1893, in Germany. Her father, Volodyslav Fedorovych, was a landowner, patron, and ambassador to the Austrian parliament. Her mother, Zdenka Elisabeth Mayer von Winthod, who died after the birth of her daughter, was an actress.

Vikonska spent her childhood and youth in Western Europe; until she was 20, she did not speak any Slavic language. She learned Ukrainian and Polish on an estate in the village of Vikno (hence her pseudonym), where she fell in love with her teacher, a professor of classical philology from Ternopil, Mykola Malytskyi, and married him against her family’s wishes. Because she defied her father and married beneath her social status, she lost most of her inheritance, except for the estate in the village of Shlyakhtyntsi, where Vikonska would write and seek peace among the plants she loved so much, as was the fashion in the period of Art Nouveau.

With the literary tradition she inherited from her family, her good education, and her erudition, Vikonska dedicated herself to intellectual pursuits. She was probably the first person in Ukraine to talk about James Joyce, writing a study in 1934 called “James Joyce: The Secret of His Artistic Face.” Her travel nonfiction includes descriptions of France, Finland, and Austria. Vikonska primarily associates herself with Venice, its well-groomed beauty, which she captures with her impressionistic style, reflecting on the city’s touristic fate, in the story “Excerpt from a Letter”:

A rebellion arose in your soul against this indulging admiration for something already worn out, long-gone, and profaned by countless tourists, just as you would reluctantly put on a beautiful second-hand dress, already worn by someone else. … But you did not know one secret that I knew: only the name of Venice is profaned. Venice itself has not lost one bit of its strange beauty because of the insolent glances of ever new visitors.

Vikonska knew the city well, attended events, and wrote reviews about the Biennale. In 1932, having visited the exhibitions in the Giardini, she, as a true decadent, did not accept futuristic trends. She had more understanding of right-wing political practices — she was indeed close to nationalist circles, including the magazine “Vistnik.”

Her sketches resemble a small room in an old estate, illuminated with soft and warm light. She sits on the window in the middle of a fierce winter, a butterfly (an image from one of her stories), “cut off from the world that interests me above all: the world of the intellectual elite.”

Her fate was tragic. After the first Soviet occupation, the family’s estates were confiscated. In 1939, when the USSR finally seized these territories, her husband was sent to the camps as an “exploiter” and died. During World War II, she went to Vienna, where on October 25, 1945, people from SMERSH, the Soviet counterintelligence unit that carried out repressions against real and potential enemies of the Soviet government, came to arrest her. Vikonska jumped out of the window to escape them and died.

Photo of Elena Kysilevska. Screenshot from YouTube channel Приватне підприємство Телерадіокомпанія НТК. Fair use.

It is worth noting that the much older Olena Kysilevska was also friends with both Yablonska and Vikonska. In 1935, Kysilevska visited Yablonska in Krynytsia and recorded an interview with her. By that time, both had already published books about their travels in Africa. Olena Kysilevska was also a great adept of solo travelling, which she saw as a mission of enlightenment and emancipation.

Olena Kysilevska was born on March 24, 1869, in the town of Monastyryska in the Ternopil region, also in a priestly family. She studied in the city of Stanislaviv (today’s Ivano-Frankivsk), joined the local women's movement, and became one of its leaders.

Later, she lived in Kolomyia, published the magazine “Women's Fate,” and was a senator in the Polish parliament for the moderate Ukrainian National Democratic Union. She wrote stories, articles, and her first artistic reportage was about Switzerland (1934). She particularly loved the sea and coastal landscapes, something that is very present in her travelogues about Morocco, the Canary Islands, the Black Sea region, and her impressions of Odessa, Yalta, Monaco, Nice, Venice, and San Remo.

But her research into Polesia, a mysterious and abandoned land at the intersection of the borders of modern Ukraine, Poland, Belarus, and Russia, a place she visited in 1934, was truly unique. “A secret country with its people, as if closed with three locks,” she wrote in her book “In the Native Land. Polesia” (1935) about her journey into this world filled with forests and swamps, gray sands and long wooden huts, waters with yellow lilies growing on the banks, ancient life and beliefs.

In this archipelago of hamlets among the swamps, which arose at the place of the melting of an ancient glacier, where the stone in the ancient lakes disappears into the bottomless depths on the longest rope, everything is uncertain: “This is a country the size of Belgium, with an area of up to one hundred thousand square kilometers. Half of it is in Poland, the other half is in Greater Ukraine, it comes right up to Kyiv. […] This is the most sparsely populated country in all of Poland, and so inaccessible with its swamps that not long before World War II, the Russian authorities were still finding places unknown to them, and people not included in the census.”

She visits places such as Kamin-Kashirsky, Bereza Kartuzka, Dorohochyn, villages and farms, travels along a narrow-gauge railway, sails on a steamer along the Oginsky Canal — a water artery built in 1767–1783, and photographs the Polishchuk water fair in Pinsk on boats. As a traveler, she sees the difficult life and needs of the local inhabitants, and searches for native, authentic exoticism.

In 1944, Olena Kysilevska left for Germany, and in 1948, emigrated to the US, where she headed the World Federation of Ukrainian Women's Organizations, wrote her memoirs and stories. She also lived in Canada, where she was buried on March 29, 1965.

Yablonska, Vikonska, and Kysilevska were free in creativity, geography, life choices, and solo travelers. They are unknown to some today, unlike a hundred years ago. These women set off on a journey of no return, and literature became their home. Although they may not have expected this, they simply mastered the art of exploring the world.

The Bridge features personal essays, commentary, and creative non-fiction that illuminate differences in perception between local and international coverage of news events, from the unique perspective of members of the Global Voices community. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the opinion of the community as a whole. All Posts

Global Voices stands out as one of the earliest and strongest examples of how media committed to building community and defending human rights can positively influence how people experience events happening beyond their own communities and national borders.

Please consider making a donation to help us continue this work.

Donate now

Authors, please log in »

Stay up to date about Global Voices and our mission. See our Privacy Policy for details. Newsletter powered by Mailchimp (Privacy Policy and Terms).

Global Voices is supported by the efforts of our volunteer contributors, foundations, donors and mission-related services. For more information please read our Fundraising Ethics Policy.

Special thanks to our many sponsors and funders.

Please support our important work:

This site is licensed as Creative Commons Attribution 3.0. Please read our attribution policy to learn about freely redistributing our work

Stay up to date about Global Voices and our mission. See our Privacy Policy for details. Newsletter powered by Mailchimp (Privacy Policy and Terms).

Global Voices is supported by the efforts of our volunteer contributors, foundations, donors and mission-related services. For more information please read our Fundraising Ethics Policy.

Special thanks to our many sponsors and funders.

Please support our important work:

The magic of travel: Three Ukrainian women writers of the 1930s – Global Voices